EXPERIENCE RESHAPING BELIEF

by Kevin Smith

IF YOU MISSED IT, PART 1 IS HERE

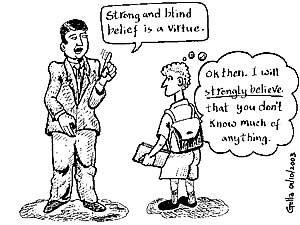

We focus on what we are experiencing, rather than what we believe. Belief is in many ways the exact opposite of experience.

We focus on what we are experiencing, rather than what we believe. Belief is in many ways the exact opposite of experience.

Belief (confidence in the truth or existence of something not immediately susceptible to rigorous proof) precedes us into our next experience and shapes that experience like a lens. So, a person who believes that black people are suspicious will go into situations with black people feeling, well, suspicious. His beliefs precede him, and when he then sees the behavior he’s hypervigilant for, he’ll say, “see? There it is. I told you.” Confirmation bias will encourage him to downplay or not notice behaviors other than the one he’s watching for.

A person with anorexia, someone who believes that she’s overweight, will walk past a mirror and feel revulsion at how fat she appears to be, even while she might actually be dying of starvation. The disease, the belief, shapes her experience like a lens.

A guy who deeply believes he is unlovable and unpopular will go into a party with a certain posture, a certain set of behaviors, that will conform his experience to his belief; people will somehow perceive him as awkward, uninteresting or unavailable, and leave him alone. Conversely, a woman who walks in confident that she is deeply lovable and interesting will often evoke, sometimes command, a response consistent with her beliefs, even if she’s not as objectively attractive as this other guy is.

So without beliefs, we’d simply experience life the way it actually is, right? Not so fast. If it were only that simple. Belief shapes what we experience, but experience also shapes what we believe. Experience, (the process of personally observing, encountering, or undergoing something) shapes belief. Or I should say it reshapes belief. I see this all the time in college students.

A white student who grew up in a racist family gets assigned to a black roommate and suddenly realizes, halfway through the semester, that this is one of the most wonderful, kind-hearted, intelligent, caring people he has ever known, a true friend. He realizes through a process called cognitive dissonance that the beliefs he has inherited from his family are the exact opposite of his actual experience, and in such a moment of realization he revises, he corrects, his beliefs. His experience tells him how his life actually is, not how he expected it would be. What he experienced and what he believed are different.

Belief comes from many different sources. We inherit some beliefs from our families and ancestors, especially systematized beliefs like religion, politics, racism, sexism, homophobia. Often these beliefs are so subtle (“Democrats are immoral” or “Republicans are greedy”) they behave more like instincts, and we don’t notice them unless we really pay attention.

We are encouraged to construct beliefs by the media, by retailers and marketers (“If I don’t have perky breasts I won’t find someone to love me” or “If I buy this car people will perceive me as successful.”) Belief can also come from mental illness or disorder. The person who sincerely believes he can fly and jumps out of a fourth story window is no less sincere in his belief than a deeply religious person who sells everything he has and gives it to the poor. The two stories have different outcomes, of course. Believing something sincerely doesn’t make it true; it’s just belief.

We construct belief from our past. Experience, however, can only exist in the now. What you think of as your “past experience” is not experience; it might be memory, analysis, opinion, or any one of another of things, but it’s not experience. Experiences you anticipate having in the future might be hopes and dreams, fears, longing, or any one of another of things, but that’s not experience. Experience is, “what’s happening right now?”

We construct belief from our past. Experience, however, can only exist in the now. What you think of as your “past experience” is not experience; it might be memory, analysis, opinion, or any one of another of things, but it’s not experience. Experiences you anticipate having in the future might be hopes and dreams, fears, longing, or any one of another of things, but that’s not experience. Experience is, “what’s happening right now?”

Belief is pretty easy to acquire; all you have to do is believe. (Peter Pan had it right!) It happens in an instant (marketers get us to do this all the time.) Experience, however, actually requires some effort, or practice. In order to perceive experience accurately (true, genuine experience) we have to pay attention. We have to ask, “what is actually happening?” One of the best tools for paying attention to our experience is a practice called mindfulness. The goal and the outcome of breath-based meditation is to be more mindful, to be more able to answer the question, “what is actually happening?”

The crux of the matter is this: belief can be true or false. Experience (genuine experience where we are clear, mindful, and paying attention to what’s actually happening) never lies. What has been told to you may or may not be true, but your actual experience is what is true for you.

The answer to the question I posed in Part 1 (how do men of many different beliefs do Touch Practice together?) is that we check our beliefs at the door and we direct our attention towards experience.

What intention are we holding towards each other right now? What am I feeling right now? How does it feel to be touched and held; how does it feel to touch and hold someone else? What do I want, what do I not want in this moment, what clues and signals is my partner giving me? How am I breathing? Where are my feet? How can I support this guy right here right now in this moment?

We might have beliefs coming into practice with each other, and we might have beliefs (sometimes revised beliefs) after we leave each other. When we’re in the room with each other, part of being grounded, centered, and mindful, is paying attention to “what’s happening right now.”

Next time you watch a heated political debate on a TV news station (it doesn’t matter whether you’re a CNN person or a FOX person, it works the same) notice how little people pay attention to “what’s happening right now.” Most children would be able to perceive, “those people are not having an effective conversation; they’re interrupting each other in the middle of sentences. They’re feeling emotions that they don’t seem to be aware of. They’re not responding to the question the person is actually asking. They seem to have come into the conversation with a script they’re trying to run.”

Next time you watch a heated political debate on a TV news station (it doesn’t matter whether you’re a CNN person or a FOX person, it works the same) notice how little people pay attention to “what’s happening right now.” Most children would be able to perceive, “those people are not having an effective conversation; they’re interrupting each other in the middle of sentences. They’re feeling emotions that they don’t seem to be aware of. They’re not responding to the question the person is actually asking. They seem to have come into the conversation with a script they’re trying to run.”

People in these kinds of intentionally polarized situations have come into the conversation with strong beliefs, and they go away with their beliefs largely unchanged. If they have any awareness of what’s actually happening during the discussion, it’s not evident to me.

In Touch Practice, we try to do the opposite. No scripts. No agendas to run. No points to prove. Just the desire to show up for each other, do no harm, touch in a way that is supportive, and pay attention to what’s happening.

I wonder what would happen in Congress if, just for a day, everyone could suspend what they believe and really pay attention to experience, to “what’s happening right now?” What if we suspended all our beliefs about global warming and focused on answering the question, “what’s actually happening?” And the Middle East?

The downside is that belief can be made neat and tidy, because belief exists only in your head. Unfortunately, experience is messy. Experience is unpredictable, it doesn’t always have the outcome you might like. It can be scary to be open to our actual experience, while clinging to a belief that we’ve built can function like a security blanket. It’s often easy to believe; it happens inside your head. Opening to your actual experience can require some courage; it happens all around you.

I suppose experience and belief dance with each other; it’s hard for me to separate them or imagine a world where both don’t operate as strong forces in our lives. But I’ll leave you with one final thought: during the Middle Ages, people who believed they were followers of Jesus tore flesh from fellow human beings with red-hot pincers, intentionally prolonging their deaths as long as possible, while other lovers-of-God looked on and cheered. They believed this is what God would have wanted, or somehow required.

I invite you to pay some attention this week to what’s actually happening, both within us and beyond us. It’s important, for all of us.