SAFETY THROUGH SEPARATION

by Kevin Smith

In various sorts of body work ranging from clinical, therapeutic massage through even the most erotic types of exchange, an explicit agreement about boundaries—where and how we will and won’t touch or be touched—is one of the ways we create a sense of safety for the participants.

In various sorts of body work ranging from clinical, therapeutic massage through even the most erotic types of exchange, an explicit agreement about boundaries—where and how we will and won’t touch or be touched—is one of the ways we create a sense of safety for the participants.

Even in relationships that are not primarily touch-based (therapist/client or teacher/student, for example) a clear and detailed understanding of boundaries—touch as well as other boundaries—contributes a great deal to making these relationships productive and healthy. Teachers often keep their private lives sequestered from students; therapists often operate within 50-minute-hour time boundaries and, similarly, are selective with how much information they share about themselves.

Why is that? Why do boundaries help to create safety, and how do they work? Let me start by looking at just a few of the dozens of boundaries which operate in our everyday lives as a way of understanding boundaries in general, and then I’ll say a bit about how boundaries of many different types—not just touch—can help make life together, physical, spiritual and otherwise, safer.

Politeness is essentially a system of boundaries, a mutually understood agreement of “where we will or won’t go.” If you get off of the elevator in the lobby of your company, and a fellow employee you barely know passes you on the way to the coffee room with a quick nod and a “how’s it going,” most people wouldn’t respond with “gosh, it’s been a really hard week; my therapist and I are really working through some deep stuff from childhood.”

Most of you know instinctively that this would be an inappropriate response somehow—but why? Because it violates a tacitly understood politeness agreement around “casual greetings by almost-strangers.” With a very close friend it might be different, but with a casual co-worker, the proper response to “how’s it going” is “fine, thanks, how are you?” There is a firm boundary about where we go (which is, basically, nowhere. “How’s it going” from a stranger is a form of greeting, not a sincere question.)

Most of you know instinctively that this would be an inappropriate response somehow—but why? Because it violates a tacitly understood politeness agreement around “casual greetings by almost-strangers.” With a very close friend it might be different, but with a casual co-worker, the proper response to “how’s it going” is “fine, thanks, how are you?” There is a firm boundary about where we go (which is, basically, nowhere. “How’s it going” from a stranger is a form of greeting, not a sincere question.)

Without that boundary, all kinds of chaos would break loose. We wouldn’t be able to predict whether encounters at the elevator would take ten seconds or ten minutes. In the interest of integrity, people would stop asking, “hey how’s it going” and simply stare straight ahead, not wanting to promise something they couldn’t deliver. Suddenly the compassionate people would start being late for meetings because they got an unpredictable response at the elevator to an interaction that had always been firmly protected by pretty sturdy boundaries.

Similarly, if someone at a department store cosmetic counter approaches you and says, “May I help you?” The response, “yes, please; my spouse has been away on a business trip and I’m SO lonely. Could you please hold me for a minute or two?” is not going to go over well. We understand implied boundaries around the offer of help; what we understand is that the offer is limited to the subject matter at hand (cosmetics sold by that particular store) and not applicable on an extended, infinite basis to your entire life.

Politeness is a system of boundaries, an agreement about where we won’t go. Politeness, while it can devolve into insincerity, is actually beneficial to organized societies. The primary role of politeness is to make routine transactions predictable. It keeps each of us from being subjected to overload from hundreds of simple, everyday decisions. Think about it: if every single time you asked someone, “how are you,” could you really handle an honest, detailed answer? Could you take as much time as the real answer took? Are you prepared to offer them all the emotional support they’d need? Probably not. “Fine, thanks” is what we’re expecting to hear.

Time is another important boundary. Suppose a good friend calls, asking, “I’d like to take you out to dinner and spend some time with you. You seem stressed and unhappy lately and I’d love to just hear how you’re doing.” You agree to meet, sit down at the restaurant, the wine is poured, dinner ordered, and then your friend leans forward and asks, “so. How’s it going?”

“Fine, thanks, how are you?”

No, the “correct” elevator response won’t work here, will it. Your friend will likely get pissed off at that response, and not because it’s impolite. What’s happening here has to do with time as a boundary.

No, the “correct” elevator response won’t work here, will it. Your friend will likely get pissed off at that response, and not because it’s impolite. What’s happening here has to do with time as a boundary.

If I asked most of you, “what’s wrong with this country,” this is a question we could discuss for two minutes, two hours, two days or two months. We could have dinner and talk about it (two hours) or we could arrange a symposium at MIT, fly in the best and brightest scholars, politicians, economic experts over a series of evening discussions (two months) or even answer, “The Republicans” or “The Democrats” (two words.) The first thing a thoughtful person would ask in response to my question, what’s wrong with this country, would be “how long do you have?”

Time is an incredibly powerful boundary. There’s a good reason why psychotherapy appointments are 50 minutes long, and it’s not because therapists are stingy; it’s because defining the time boundary allows people to plan and pace the expenditure of their emotional and psychological resources so that they don’t “overspend” themselves in the process of self-disclosure. Meetings that start on time and stop on time don’t necessarily result from rigid, inflexible leadership; on the contrary. Making the start and stop times of group process work clear can be a tremendous source of support if the group is doing difficult work, because it eliminates unnecessary unpredictability, limits ambiguity, which allows the group to dedicate emotional resources to the work at hand.

As humans, we have limited capacity for ambiguity. Creative people have, in general, a higher capacity for ambiguity; traumatized people, in general, a somewhat compromised capacity. We can’t go into every encounter at the elevator or the grocery store with an unlimited possibility of outcomes; it’s too much for us. We have to establish some limits somewhere.

And so it is with body work, and Touch Practice in particular. I always recommend that people who adopt or adapt a personal Touch Practice for themselves operate within a time limit, typically an hour or 90 minutes at most. I always recommend an explicit, honest and sincere discussion to agree upon touch boundaries you intend to hold.

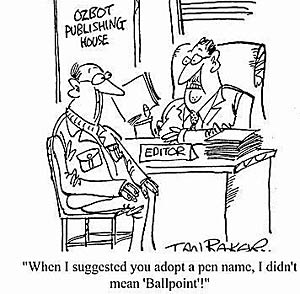

Even pseudonyms, which many people I work with use, and which many people feel shame around, can be a healthy form of boundary, and I encourage people to work with these as protective and functional rather than shameful whenever possible.

I use the pseudonym Kevin Smith because I want to make myself public, vulnerable and extremely open and available around this work, but I also want to establish a protective boundary around my parents, my career, my spouse, my kids, my home address and phone number, and everything else that would be vulnerable were I to use my actual name.

I use the pseudonym Kevin Smith because I want to make myself public, vulnerable and extremely open and available around this work, but I also want to establish a protective boundary around my parents, my career, my spouse, my kids, my home address and phone number, and everything else that would be vulnerable were I to use my actual name.

Many people who come to me under a pseudonym want to explore being touched without placing their marriage, their home address and phone number, their job, etc., on the line. Should all of that disclosure be required just to get held? For heaven’s sake: use a different name, please! Pseudonyms, consciously and conscientiously used, can be a skillful and integral part of how we keep ourselves safe through the use of boundaries. They can be an expression of integrity, or can come from shame or deceit. The difference is the intention and awareness with which they are used.

Pseudonyms, time limits, body boundaries, limits around self-disclosure (“what do you do for a living? where do you live? are you married or single?”) are all useful, appropriate, and healthy, if used consciously and intentionally, rather than impulsively and shamefully. Skillful construction of boundaries is a way to control ambiguity, to make ourselves vulnerable to a healthy but carefully defined extent, to engage a partner in a limited, intentional and conscientious interaction, and thus to create safety.

My sincere recommendation is that there’s no need to bare your entire heart in order to take a step toward wholeness. On the contrary. Go forth and create boundaries! Create as many of them as you need to feel safe, in whatever ways and places you need them. Don’t do it from shame. Don’t do it compulsively or without thinking about it, but because you understand that the ability to open up, share yourself and let go is intimately connected with the ability to establish boundaries, to fence yourself off. If you can do one, you can do the other; if you can’t do one, you can’t do either...