The Descent into Hell

Now there’s a catchy little title for a Spring blog. Got your attention?

I’m mindful this weekend that it’s Easter. I am struck by one version of the resurrection story (enshrined in later revisions of what is now known as the Apostles’ Creed) that in between his death and resurrection, Jesus spent some time in hell.

This reminds me of another story, this one about the Buddha as he was sitting, seeking enlightenment. Mara, a hideous demon, “sends an army of revolting and terrible creatures, bent on the bodily destruction of Buddha. They launch a volley of arrows at Buddha, but as these projectiles approach they are transformed into flowers and fall harmlessly to the ground.”

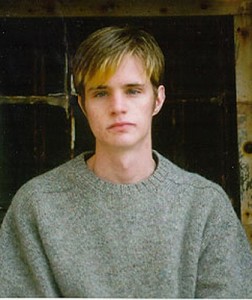

And that, in turn, reminds me of many different Greek myths, countless warriors, travelers and ordinary people facing their own set of demons, arrows and tortures. It reminds me of Jonah sitting in the belly of the whale, of Matthew Shepherd hanging on a fence, of the Apollo 13 astronauts limping back to earth in a crippled capsule balanced treacherously between death-by-oxygen-starvation or death-by-incineration. Incidentally, their ordeal, like that of Jesus and Jonah, seemed to last exactly three days. Unfortunately, our dear brother Matthew suffered twice as long, although as I re-read the chronology of his terrible ordeal, it seems probable that he was only conscious for about three days of it.

And that, in turn, reminds me of many different Greek myths, countless warriors, travelers and ordinary people facing their own set of demons, arrows and tortures. It reminds me of Jonah sitting in the belly of the whale, of Matthew Shepherd hanging on a fence, of the Apollo 13 astronauts limping back to earth in a crippled capsule balanced treacherously between death-by-oxygen-starvation or death-by-incineration. Incidentally, their ordeal, like that of Jesus and Jonah, seemed to last exactly three days. Unfortunately, our dear brother Matthew suffered twice as long, although as I re-read the chronology of his terrible ordeal, it seems probable that he was only conscious for about three days of it.

This blog is for anyone who has ever felt, or uttered, the words, “My God, my god, why have you forsaken me?”

And that, I suspect, is virtually all of us, at one time or another. Any of us who have taken the epic journey, whether inward to our deepest fears and worst feelings, or outward, like Odysseus (both journeys lead the same place) has likely encountered this space, this feeling of “I am in here (or out here, or down here) all alone. There is no rescue in sight. There is no hope for me.” It doesn’t necessarily happen at the end of our life; we get little tastes of it all along the journey. ( I’ve written about my own personal little taste of “the descent into hell” in my blog entry “Insides Out.”)

And that, I suspect, is virtually all of us, at one time or another. Any of us who have taken the epic journey, whether inward to our deepest fears and worst feelings, or outward, like Odysseus (both journeys lead the same place) has likely encountered this space, this feeling of “I am in here (or out here, or down here) all alone. There is no rescue in sight. There is no hope for me.” It doesn’t necessarily happen at the end of our life; we get little tastes of it all along the journey. ( I’ve written about my own personal little taste of “the descent into hell” in my blog entry “Insides Out.”)

If you notice a pattern, or commonalities, to these stories, whether they be true or mythic stories, you’re not alone. Some have described a kind of template using the phrase “Hero’s Journey,” a set of steps or phases of work that we do on our path to wholeness. Perhaps I should even say, “our path to greatness.”

One aspect of that Hero’s Journey is the journey inward, the journey inside to what we feel and experience. We can expend enormous effort to avoid the journey inside: many of us do not want to get on that particular boat.

We overeat, we overdrink, we blame, shame, and scapegoat, and we engage in all variety of addictive behavior. We flee loneliness by hooking up; we thwart boredom with recreational drugs; we run from tensions at home through the companionship of the constantly-on television or the bottle of wine. We attempt to avoid feelings of inadequacy by buying the better car or the larger flat-screen or trading in our partner for a younger, newer model.

We can avoid our journey inwards simply by speaking or thinking about it too much. Some talk incessantly about their experience in order to avoid having to feel it. Still others “think it up,” devising elaborate theologies or systematized ways of overthinking, so that they can avoid feeling.

Nazis left volumes and volumes of intricate, detailed pseudo-scientific writings about how and why they “needed” to do what they did. The unimaginable tortures of the Middle Ages’ Inquisition were defended by incredibly rococo theology and tediously thought-out rationalizations explaining how tearing someone’s flesh with red-hot pincers was somehow an expression of devotion to God. We are capable of thinking our way around our experience, thinking in order to avoid what we feel. It happens all the time.

Just consider the number of incredibly well-thought out reasons we have given ourselves for not taking care of our own poor. There are a hundred and one (at least) justifications as to why we cannot feed, house and clothe our own people. They’re very well written out. They’re very lengthy. The thinking is very good. Makes a lot of sense. We each have our own utterly convincing arguments, all based in thinking. Most of us have someone in mind to blame. But let’s turn back to experience.

How does it feel that we have 65 inch flat-screen TV’s and little kids with empty bellies. How does it feel that the average household now has more televisions than people, but many households don’t have enough food or clothing or medical care for their kids. Don’t think; don’t explain; don’t defend; don’t blame. How does that feel. How does it feel. How does it feel.

We avoid the journey inward in many different ways, but there’s another big one: we medicate. Now, to be clear: I have no doubt that people with some serious mental health issues such as bipolar disorder or long-term depression may in many cases benefit from medications that are available. I am not anti-medication.

But I also believe, as a culture, we medicate too often, too quickly, and in a way that, at times, thwarts the journey. Medication has become a first responder rather than a last resort. If the Buddha had shared with his therapist that he was intending to go out and sit under a tree until he felt better, a prescription might, tragically, have kept him comfy and complacent on his couch instead. Odysseus would have been medicated back to his senses (“why even get into that boat to begin with?”) And does every difficult childhood experience need to be medicated? Does every restless or fidgety child earn a pill? Perhaps for some, medication helps; for others, which journeys have we denied them, which voyages?

We too often consider difficult feelings a malady to be treated and cured. But sometimes difficult feelings are a call to the journey. A hero’s journey. A journey that transforms and redeems our experience. Difficult feelings can be a gift, a guide, the opening to the other world, a world of transformation and redemption. Some cultures have traditions where these journeys are actually encouraged and induced, such as the tradition of the vision quest carried by many indigenous people. Difficult feelings can be a passageway or a carrier. We can run from them, or we can get on them and ride them like a horse.

I want to say that if we will fully embrace this life, we cannot avoid the descent into hell. But from what I see, and what I have experienced, hell is a place we move through, sometimes in three days or so, if we’ll really let ourselves go there and check in for the stay. The process of facing our darkest fears is just that: process. It’s not a destination; it’s a way of being with something in a way that transforms it into something else.

What helps? Getting support helps. The work, because of its nature, is work we each do by ourselves–part of what makes hell hellish is that we’re all alone in that place. However, there is support.

In every version of the Hero’s Journey story, there are supernatural forces allied with us. Indigenous people often have spirit advocates in the form of animals; theistic people have many different versions of higher spirits. Even in the language of recovery and addition, the Second Step mentions “a power greater than ourselves.” (While Step Four may not be hell, most people in recovery would not describe it as a festive place, either. The descent into a place where we face things we would rather not look at takes many different forms and has many different names.)

In every version of the Hero’s Journey story, there are supernatural forces allied with us. Indigenous people often have spirit advocates in the form of animals; theistic people have many different versions of higher spirits. Even in the language of recovery and addition, the Second Step mentions “a power greater than ourselves.” (While Step Four may not be hell, most people in recovery would not describe it as a festive place, either. The descent into a place where we face things we would rather not look at takes many different forms and has many different names.)

The support of our higher powers, however we name them, is essential. We can also support ourselves, through grounding and awareness practices, breath-based meditation, prayer, mindfulness practice. These practices enlarge and enhance our ability to sit with what we feel.

And we can support each other. This is complicated and requires discernment. I have found that I can talk to others about my fears or feelings in order to then turn and do my own work: or instead of doing my own work. Some take medication to make it more comfortable to face what they are feeling; some take it to avoid facing what they are feeling. There are ways we have of offering each other support on the journey, but ultimately, we still have to do our own work. Even when I’m holding someone in Touch Practice, which can be of tremendous support, I can’t go inside to their feelings and go with them. Even when I have my arms around someone tightly, he’s inside with his feelings alone.

I want to suggest to you that hell is not a place but a process; that it is not a form of punishment but a period of transformation, and that it is both incredibly intense and remarkably brief if–and this is a big if–we can allow ourselves to go there, to fully show up, to breathe it in. Like Mara’s arrows, the things coming at us which appear to threaten our lives very quickly lose their power when we stop defending ourselves against them.

And the good news about your visit to hell? Unlike spending three days in Maui, you don’t need to put a lot of effort into planning what to do, where to go and what to see once you’re there. Just show up. The work does itself, if we can just sit with it and make space for it. The work consists entirely of feeling our feelings, noticing our experience. Once we can feel our discomfort, without resisting it, pushing it away, medicating it to dull it down or explaining or blaming it away–once what we feel and experience becomes a genuine, integrated part of us, the work is largely done, making way for new insights and new connections.

Have thoughts you’d like to share?

Touch Practice is a sacred practice for me, and part of that is keeping confidences sacred. While a name and e-mail address are required to post a comment, feel free to use just your first name, or a pseudonym if you wish. Your e-mail address will never be seen by or shared with anyone. It is used to prevent spam and inappropriate comments from appearing in the blog. I’d really like to hear from you!

Thanks once again for your insights as well as your good timing. First, some thoughts on Holy Saturday from Richard Rohr, a Franciscan priest: “Jesus trusted enough to outstare the darkness, to outstare the void, to hold out for the resurrection of the forever-awaited “third day,” and not to try to manufacture His own. That is how God stretches and expands the soul….

You see, to love fully is to die! (When you fully unite with the other, the separate self is gone.) What is handed over to God is always returned to us transformed into Christ Consciousness. Easter is the eternal third day that we forever await, but today we are content to live in the belly of the whale, in liminal space, in the “in between” that is most of human life. God is creating a Big Space inside of you. Just wait!”

I just want to add a personal word. A week from Monday I leave for my own “journey:” –a month in Spain walking the 500 mile pilgrimage: Camino de Santiago de Compostela. Much love to all you IN TOUCH pilgrims! We each walk our own journey in solidarity with each other and with the earth.

Gary, a Happy Easter to you and, most especially, prayers and blessings for your pilgrimage. What an ancient and wonderful spiritual practice that is. May each and every step bring a gift. Big hugs to you.

Timely indeed. Just last night in an evensong service, I read out loud ‘he descended into hell’ and I wondered, perhaps for the first time – what this meant. So here, you’ve given me lots to think about, Kevin. Thank you.

Tony–blessings to you and wishes for a joyous Easter!